The Day of Vow – South Africa – The Battle of Blood River – 16 December 1838

The original article below can be viewed at: Day Of The Vow – Events in South Africa (trek.zone)

Day of the Vow

The Day of the Vow was a religious public holiday in South Africa. It is an important holiday for Afrikaners, originating from the Battle of Blood River on 16 December 1838.

Initially called Dingane’s Day (Afrikaans: Dingaansdag), 16 December was made an annual national holiday in 1910, before being renamed Day of the Vow in 1982.

In 1994, after the end of Apartheid, it was replaced by the Day of Reconciliation, an annual holiday also on 16 December.

Origin

The day of the Vow traces its origin as an annual religious holiday to The Battle of Blood River on 16 December 1838. The besieged Voortrekkers took a public vow (or covenant) together before the battle, led by Sarel Cilliers. In return for God’s help in obtaining victory, they promised to build a church and forever honour this day as a holy day of God. They vowed that they and their descendants would keep the day as a holy Sabbath. During the battle a group of about 470 Voortrekkers defeated a force of about 20,000 Zulu. Three Voortrekkers were wounded, and some 3,000 Zulu warriors died in the battle.

Two of the earlier names given to the day stem from this prayer. Officially known as the Day of the Vow, the commemoration was renamed from the Day of the Covenant in 1982. Afrikaners colloquially refer to it as Dingaansdag (Dingane’s Day), a reference to the Zulu ruler of the defeated attackers.

Wording

No verbatim record of the vow exists. The version often considered to be the original vow is in fact W.E.G. Louw’s ca. 1962 translation into Afrikaans of G.B.A. Gerdener’s reconstruction of the vow in his 1919 biography of Sarel Cilliers (Bailey 2003:25).

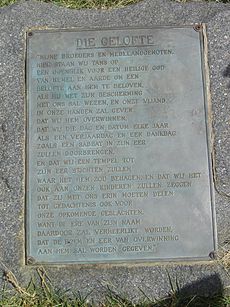

The wording of the Vow is:

-

Afrikaans: Hier staan ons voor die Heilige God van Hemel en aarde om ʼn gelofte aan Hom te doen, dat, as Hy ons sal beskerm en ons vyand in ons hand sal gee, ons die dag en datum elke jaar as ʼn dankdag soos ʼn Sabbat sal deurbring; en dat ons ʼn huis tot Sy eer sal oprig waar dit Hom behaag, en dat ons ook aan ons kinders sal sê dat hulle met ons daarin moet deel tot nagedagtenis ook vir die opkomende geslagte. Want die eer van Sy naam sal verheerlik word deur die roem en die eer van oorwinning aan Hom te gee.

-

English: We stand here before the Holy God of heaven and earth, to make a vow to Him that, if He will protect us and give our enemy into our hand, we shall keep this day and date every year as a day of thanksgiving like a sabbath, and that we shall build a house to His honour wherever it should please Him, and that we will also tell our children that they should share in that with us in memory for future generations. For the honour of His name will be glorified by giving Him the fame and honour for the victory.

History

Photo: Renier Maritz / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / en.wikipedia.org

The official version of the event is that a public vow was taken – The Covenant Vow on Sunday, 09th Dec. 1838 – It was at this Wasbank laager where Pretorius, Landman and Cilliers formulated “The Vow” and recorded by Bantjes (pages 54-55 of his journal – location of Wasbank, S28° 18′ 38.82 E30° 8′ 38.55). The original Bantjes words from the journal read as follows; “Sunday morning before service began, the Commander in Chief (Pretorius) asked those who would lead the service to come together and requested them to speak with the congregation so that they should be zealous in spirit, and in truth, pray to God for His help and assistance in the coming strike against the enemy, and tell them that Pretorius wanted to make a Vow towards the Almighty (if all agreed to this) that “if the Lord might give us victory, we hereby promise to found a house (church) as a memorial of his Great Name at a place (Pietermaritzburg) where it shall please Him”, and that they also implore the help and assistance of God in accomplishing this vow and that they write down this Day of Victory in a book and disclose this event to our very last posterities in order that this will forever be celebrated in the honour of God.”

This bound future descendants of the Afrikaner to commemorate the day as a religious holiday (sabbath) in the case of victory over the Zulus by promising to build a church in God’s honour. By July 1839 nothing had yet been done at Pietermaritzburg regarding their pledge to build a church, and it was Jan Gerritze Bantjes himself who motivated everyone to keep that promise. In 1841 with capital accumulated by Bantjes at the Volksraad, the Church of the Vow at Pietermaritzburg was eventually built – the biggest donor being the widow, Mrs. H.J.van Niekerk in Sept. 1839.

As the original vow was never recorded in verbatim form, descriptions come only from the diary of Jan Bantjes with a dispatch written by Andries Pretorius to the Volksraad on 23 December 1838; and the recollections of Sarel Cilliers in 1871. A participant in the battle, Dewald Pretorius also wrote his recollections in 1862, interpreting the vow as including the building of churches and schools (Bailey 2003:31).

Jan B. Bantjes (1817–1887), Pretorius’ secretary, indicates that the initial promise was to build a House in return for victory. He notes that Pretorius called everyone together in his tent, (the senior officers) and asked them to pray for God’s help. Bantjes writes in his journal that Pretorius told the assembly that he wanted to make a vow, “if everyone would agree” (Bailey 2003:24). Bantjes does not say whether everyone did so. Perhaps the fractious nature of the Boers dictated that the raiding party held their own prayers in the tents of various leading men (Mackenzie 1997:73). Pretorius is also quoted as wanting to have a book written to make known what God had done to even “our last descendants”.

Pretorius in his 1838 dispatch mentions a vow (Afrikaans: gelofte) in connection with the building of a church, but not that it would be binding for future generations.

we here have decided among ourselves . . . to make known the day of our victory . . . among the whole of our generation, and that we want to devote it to God, and to celebrate with thanksgiving, just as we . . . promised in public prayer

Contrary to Pretorius, and in agreement with Bantjes, Cilliers in 1870 recalled a promise (Afrikaans: belofte), not a vow, to commemorate the day and to tell the story to future generations. Accordingly, they would remember:

the day and date, every year as a commemoration and a day of thanksgiving, as though a Sabbath . . . and that we will also tell it to our children, that they should share in it with us, for the remembrance of our future generations

Cilliers writes that those who objected were given the option to leave. At least two persons declined to participate in the vow. Scholars disagree about whether the accompanying English settlers and servants complied (Bailey 2003). This seems to confirm that the promise was binding only on those present at the actual battle. Mackenzie (1997) claims that Cilliers may be recalling what he said to men who met in his tent.

Up to the 1970s the received version of events was seldom questioned, but since then scholars have questioned almost every aspect. They debate whether a vow was even taken and, if so, what its wording was. Some argue that the vow occurred on the day of the battle, others point to 7 or 9 December. Whether Andries Pretorius or Sarel Cilliers led the assembly has been debated; and even whether there was an assembly. The location at which the vow was taken has also produced diverging opinions, with some rejecting the Ncome River site for (Bailey 2003).

Commemorations of the Day of the Vow

Photo: Theo V. BreslerUploaded by Theobresler at en.wikip / CC BY-SA 3.0 / en.wikipedia.org

Disagreements exist about the extent to which the date was commemorated before the 1860s. Some historians maintained that little happened between 1838 and 1910. Historian S.P. Mackenzie argues that the day was not commemorated before the 1880s. Initial observations may have been limited to those associated with the battle at Ncome River and their descendants. While Sarel Cilliers upheld the day, Andries Pretorius did not (Ehlers 2003).

In Natal

Informal commemorations may have been held in the homes of former Voortrekkers in Pietermaritzburg in Natal. Voortrekker pastor Rev. Erasmus Smit announced the “7th annual” anniversary of the day in 1844 in De Natalier newspaper, for instance. Bailey mentions a meeting at the site of the battle in 1862 (Bailey 2003:29,32).

In 1864 the General Synod of the Dutch Reformed Church in Natal decreed that all its congregations should observe the date as a day of thanksgiving. The decision was spurred by the efforts of two Dutch clergymen working in Pietermaritsburg during the 1860s, D.P.M. Huet and F. Lion Cachet. Large meetings were held in the church in Pietermaritzburg in 1864 and 1865 (Bailey 2003:33).

In 1866 the first large scale meeting took place at the traditional battle site, led by Cachet. Zulus who gathered to watch proceedings assisted the participants in gathering stones for a commemorative cairn. In his speech Cachet called for the evangelisation of black heathen. He relayed a message received from the Zulu monarch Cetshwayo. In his reply to Cetshwayo, Cachet hoped for harmony between the Zulu and white Natalians. Trekker survivors recalled events, an institution which in the 1867 observation at the site included a Zulu (Bailey 2003:35).

Huet was of the same opinion as Delward Pretorius. He declared at a church inauguration in Greytown on 16 December 1866 that its construction was also part of fulfilling the vow (Bailey 2003:35).

In the Transvaal

Die Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek declared 16 December a public holiday in 1865, to be commemorated by public religious services. However, until 1877, the general public there did not utilise the holiday as they did in Natal. Cricket matches and hunts were organised, some businesses remained open, and newspapers were sold. The name Dingane’s Day appeared for the first time in the media, in an 1875 edition of De Volksstem. That newspaper wondered whether the lack of support for the holiday signalled a weakening sense of nationalism (Bailey 2003:37,38).

After the Transvaal was annexed by the British in 1877, the new government refrained from state functions (like Supreme Court sittings) on the date (Bailey 2003:41).

The desire by the Transvaal to retrieve its independence prompted the emergence of Afrikaner nationalism and the revival of 16 December in that territory. Transvaal burgers held meetings around the date to discuss responses to the annexation. In 1879 the first such a meeting convened at Wonderfontein on the West Rand. Burgers disregarded Sir G.J. Wolseley, the governor of Transvaal, who prohibited the meeting on 16 December. The following year they held a similar combination of discussions and the celebration of Dingane’s Day at Paardekraal (Bailey 2003:43).

Paul Kruger, president of the Transvaal Republic, believed that failure to observe the date led to the loss of independence and to the first Anglo-Boer war as a divine punishment. Before initiating hostilities with the British, a ceremony was held at Paardekraal on 16 December 1880 in which 5,000 burghers piled a cairn of stones that symbolized past and future victories (over the Zulu and the British).

After the success of its military campaign against the British, the Transvaal state organised a Dingane’s Day festival every five years. At the first of these in 1881, an estimated 12,000 to 15,000 people listened to speeches by Kruger and others (Gilliomee 1989). At the third such festival in 1891, Kruger emphasised the need for the festival to be religious in nature (Ehlers 2003).

In the Free State

The Free State government in 1894 declared 16 December a holiday (Bailey 2003).

National commemorations

The Union state in 1910 officially declared Dingane’s Day as a national public holiday.

In 1938 D.F. Malan, leader of the National Party, reiterated at the site that its soil was “sacred.” He said that the Blood River battle established “South Africa as a civilized Christian country” and “the responsible authority of the white race”. Malan compared the battle to the urban labour situation in which whites had to prevail (Ehlers 2003).

In 1952 the ruling National Party passed the Public Holidays Act (Act 5 of 1952), in which section 2 declared the day to be a religious public holiday. Accordingly, certain activities were prohibited, such as organized sports contests, theatre shows, and so on (Ehlers 2003). Pegging a claim on this day was also forbidden under section 48(4)(a) of the Mining Rights (Act 20 of 1967; repealed by the Minerals Act (Act 50 of 1991). The name was changed to the Day of the Vow in order to be less offensive, and to emphasize the vow rather than the Zulu antagonist (Ehlers 2003).

In 1961 the African National Congress chose 16 December to initiate a series of sabotages, signalling its decision to embark on an armed struggle against the regime through its military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe.

In 1983 the South African government vetoed the decision by the acting government of Namibia to discontinue observing the holiday. In response, the Democratic Turnhalle Alliance resigned its 41 seats in Namibia’s 50-seat National Assembly.

Act 5 of 1952 was repealed in 1994 by Act No. 36 of 1994, which changed the name of the public holiday to the Day of Reconciliation.

Act 8 of 1995 offered a compensation to the families of the three Voortrekkers who were wounded.

Debates over the Holiday

Scholars like historian Leonard Thompson have said that the events of the battle were woven into a new myth that justified racial oppression on the basis of racial superiority and divine providence. Accordingly, the victory over Dingaan was reinterpreted as a sign that God confirmed the rule of whites over black Africans, justifying the Boer project of acquiring land and eventually ascending to power in South Africa. In post-apartheid South Africa the holiday is often criticised as a racist holiday, which celebrates the success of Boer expansion over the black natives.

By comparison with the large number of Afrikaners who participated in the annual celebrations of the Voortrekker victory, some did take exception. In 1971, for instance, Pro Veritate, the journal of the anti-apartheid organisation the Christian Institute of Southern Africa, devoted a special edition to the matter.

Historian Anton Ehlers traces how political and economic factors changed the themes emphasised during celebrations of the Day of the Vow. During the 1940s and 1950s Afrikaner unity was emphasised over against black Africans. This theme acquired broader meaning in the 1960s and 1970s, when isolated “white” South Africa was positioned against the decolonisation of Africa. The economic and political crises of the 1970s and 1980s forced white Afrikaners to rethink the apartheid system. Afrikaner and other intellectuals began to critically evaluate the historical basis for the celebration. The need to include English and “moderate” black groups in reforms prompted a de-emphasis on “the ethnic exclusivity and divine mission of Afrikaners” (Ehlers 2003).

Based on: Wikipedia

Related Blogposts

-

16th December The Day of The Vow | Luke 9:23 Evangelism (wordpress.com) (December 16, 2011)

-

The Day of The Vow | Luke 9:23 Evangelism (wordpress.com) (December 16, 2021)

Filed under: Christianity, Day of The Vow, History | Tagged: Battle of Blood River, Dingaan, South Africa, Voortrekkers, Zulus | Leave a comment »

To view this presentation with pictures as a PowerPoint on Slideshare, click

To view this presentation with pictures as a PowerPoint on Slideshare, click  On Tuesday morning William Wood, a young English trader fluent in Zulu, who was visiting the Owens, warned Retief that “your entire party will be massacred before the day is out.” As the Retief party struck camp and were preparing to leave, they were invited to a final farewell display. For this they were requested to leave their firearms, bandoleers and powder horns outside the gates of the kraal. Incredibly, they acceded to this demand. Leaving their firearms outside the kraal, they walked defenceless into the arena of Dingaan’s kraal. After ominous war dances which increased in volume and intensity, Dingaan stood up and shouted “Babulaleni abathakathi!” (“kill the wizards!”).

On Tuesday morning William Wood, a young English trader fluent in Zulu, who was visiting the Owens, warned Retief that “your entire party will be massacred before the day is out.” As the Retief party struck camp and were preparing to leave, they were invited to a final farewell display. For this they were requested to leave their firearms, bandoleers and powder horns outside the gates of the kraal. Incredibly, they acceded to this demand. Leaving their firearms outside the kraal, they walked defenceless into the arena of Dingaan’s kraal. After ominous war dances which increased in volume and intensity, Dingaan stood up and shouted “Babulaleni abathakathi!” (“kill the wizards!”). _________________________________

_________________________________

This heart gripping piece of history about The Battle of Blood River as related by Deirdre Fields must be told to the Aryans of the world, as at this moment again we are faced by overwhelming odds:

This heart gripping piece of history about The Battle of Blood River as related by Deirdre Fields must be told to the Aryans of the world, as at this moment again we are faced by overwhelming odds:

Joshua Project

Joshua Project The Biblical Basis of Missions

The Biblical Basis of Missions

![The Biblical Nativity (Birth) of our Lord Jesus Christ according to the Holy Scriptures in the Gospel of Luke 1 & 2 [see Purge the leaven … blog post] The Nativity of our Lord Jesus Christ ~ Luke 1 & 2 The Biblical Nativity (Birth) of our Lord Jesus Christ according to the Holy Scriptures in the Gospel of Luke 1 & 2 [see Purge the leaven … blog post]](https://luke923evangelism.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/birth-of-christ-e1374168223523.png)